From antiquity up to a few hundred years ago, it was understood by nearly all human beings that the sun revolved around the earth. This made sense because, as we were the center of consciousness, creation and the universe itself, the cosmos should logically be set up as a backdrop to humanity. Thinking otherwise was heresy for some and discouraged for all.

It was a huge paradigm shift when our Earth was shown to have something other than a starring role in the grand scheme, and is to some extent still being played out. The current orthodoxy is that although we were placed on an out-of-the-way planet nowhere near the center of our galaxy, our species is still the be-all and end-all of creation, or at least, failing that, of consciousness.

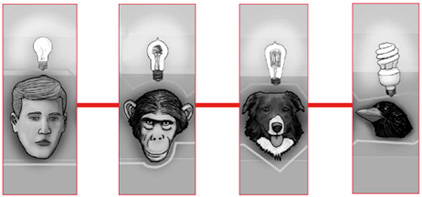

Now, within the last couple of decades, our mantra “that’s what separates us from the animals,” or what I call “human supremacy,” has been assailed by new science on animal behavior. Within even the last couple of years this credo has been forced to stake out more complex positions on higher ground as the floodwaters of reality have swamped our previous outposts.

Since the dawn of time, we were supposedly the only animals with a real language. By the 20th century that notion was already discredited, and our claim to distinction became “Man the Tool-Maker.” First we were the only animals that used tools, then when that was knocked down, the only animal that made tools. With documentary evidence of chimpanzees fashioning and using termite-scooping tools in rotting logs, that fell by the wayside as well.

It’s a good thing the defenders of unique humanity didn’t loudly proclaim that they might have tools, but we have entire tool kits, because it’s just come to light that certain chimps also use multiple self-fashioned tools on a given job. “Using infrared, motion-triggered video cameras,” National Geographic reported, “researchers have documented how chimpanzees in the Republic of Congo use a variety of tools to extract termites from their nests.”

“The new video cameras revealed chimps using one short stick to penetrate the aboveground mounds and then a ‘fishing probe’ to extract the termites,” the story continued. “For subterranean nests the chimps use their feet to force a larger ‘puncturing stick’ into the earth, drilling holes into termite chambers, and then a separate fishing probe to harvest the insects. Often the chimps modified the fishing probe, pulling it through their teeth to fray the end like a paintbrush. The frayed edge was better for collecting the insects.” Pat Wright, a primatologist with New York State’s Stony Brook University commented that “It’s exciting to watch these chimps do something that we’ve seen only people do before – use their feet to push the stick into the ground as a farmer might do with a shovel.”

Even lower primates have shown higher mentality than expected in recently devised tests. Last year, capuchin monkeys were taught to swap tokens for food. “Normally, capuchins were happy to exchange their tokens for cucumber. But if one monkey was given a cucumber while the other got a (tastier) grape for the same token, the first monkey rebelled. Some refused to pay, others took the cucumber but refused to eat it. The animal’s umbrage was even greater if the other monkey was rewarded for doing nothing. They did more than sulk, sometimes throwing the food out of their cage,” reported the Telegraph. The capuchin study reveals an emotional sense of fairness plays a key role in [economic] decision-making, said Sarah Brosnan of the Yerkes National Primate Research Centre of Emory University. This sense of equality may be common among social primates, the article added.

And while it’s often easy to see, and easy for human supremacists to concede, similarities between our behavior and that of other primates, people who ascribe what are considered human characteristics to their animal companions are known to be “anthropomorphizing.” Or at least they were – one of the key assertions that cat and dog people make, that their animals have distinct personalities, has just been scientifically established. Discovery News reported late last year about a cross-species personality published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, showing that dogs have personalities, and that these character traits can be identified as accurately as similar personality attributes in humans. “Dogs,” the article notes, “were chosen because of their wide availability, the fact that they safely and naturally exhibit a wide variety of behaviors, are understood well by many humans, and can travel to research sites with ease. Experts, however, suspect that many other animals also possess unique personalities.”

Well, personalities, yes, but can dogs think? Now, whether the dog who recently saved her owner’s life by calling 911 and barking incessantly into the phone receiver was “thinking” may be arguable. Certainly the puppy who managed to shoot the man who was killing the whole litter was just a lucky shot. But these anecdotes, and others, are not the only indications of the capabilities of companion animals.

In June, the journal Science reported that “A German border collie named Rico has learned 200 words, indicating that a dog’s ability to understand language is far better than expected.” A Bloomberg News story goes on to explain that Rico “correctly retrieved 37 out of 40 toys by name.” Here’s the kicker: “The dog was given the names of the toys just once.”

Do you speak German? If not, pretend you’re given German words for 40 objects, hearing each word only once. Would you then be able to match more than 37 of them? I’m pretty sure most non-German speakers, including me, wouldn’t even come close. What does that tell us?

Any one of these incidents puts a serious dent in the concept of human supremacy, if only because it shows that our previous assumption about the line delineating human consciousness from (non-human) animal consciousness is not where we thought it was and calls into question our ability to judge the issue dispassionately. But the pull of speciesism is strong, and the human brain is powerful and adaptable enough to generate new rationalizations on the fly: Primates are close to us genetically, and dogs and cats are close to us domestically, so sure, those animals might be the exceptions that prove the rule, but the rule still stands: You don’t see other, lower animals making tools, for instance.

But even that assurance was torpedoed two years ago, when “Betty the Crow” surprised tool-usage researchers by making her own tool to complete a task. Researchers wondered whether she would know to pick a hooked wire rather than a straight one to successfully lift a small jar from a tube to get at food. When her companion flew off with the hooked wire, Betty took the straight wire and bent it into a hook and retrieved the food – then she repeated this nine out of ten times in subsequent experiments.

In short, all this time it may have been our own inability to measure and comprehend the thought processes of birds (for instance) that has made the expression “bird brain” so derogatory. A recent Christian Science Monitor article begins with a humorous admission of this: “Bird brains seem to be smarter these days.” Less ironically, it continues: “Scientists are finding hints of a higher level of intelligence than expected as they look more closely at our avian friends.” A pair of studies on finches and jays showed the birds grasping more about their social situation and acting more upon it than scientists had assumed they could.

Similarly, news from the world of squirrels shows that there may be realms of intellect, socializing, and language that we have so far not been privy to because they work, literally, on a different wavelength. Using video cameras and a special ultrasonic device, Canadian researchers discovered that Richardson’s Ground Squirrels were warning each other about predators by means of high-pitched squeals inaudible to humans and probably most of the squirrels’ predators as well. “They’re able to discriminate among callers based on their calls, and they can communicate fairly specific information,” said zoologist David Wilson, who speculates that the content of the squirrels’ vocalizing “may include detailed information about the squirrels’ predators.”

A similarly-constructed study reported in November found sea animals virtually translating what entirely different species are saying: Seals, dolphins, and other marine mammals listen to the voice patterns of killer whales and can distinguish between two social classes of the same species of whale, knowing when to get out of the way of those that are hunting. An article in Discovery says these findings “could suggest marine mammals translate what the whales are saying,” and although lead author Volker Deecke resists putting it that strongly, he does go on to mention that “forest monkeys can decipher the alarm call of another monkey species, and hornbills, a tropical forest bird, can decipher monkey and eagle alarm calls.” The question might arise of how well human efforts to decipher other animals’ communication compare with these.

One line of delineation that persists even in discussion by some animal rights activists essentially excludes farm animals from true consideration in the intellectual community. Unsurprisingly, not many cognitive experiments are done on Holsteins or pigs. But even our poster child for the concept of “dumb animal,” the sheep, has been shown to be able to remember up to 50 different sheep faces for more than two years, as well as recognizing human faces. (How many sheep faces can you tell apart, by the way?)

And the more we look at even “lower” animals than that, the more we discover about the limitations of our own understanding. Fish, it turns out, “possess cognitive abilities outstripping those of some small mammals,” reports the Sunday Telegraph. With tests of memory and cognition that had previously been untried, Dr. Theresa Burt de Perera found that fish are “very capable of learning and remembering, and possess a range of cognitive skills that would surprise many people.”

Well, no matter what, we can fall back on our unique sense of self, though, right? Animals may be conscious of many things in the world around them, more things than we may have previously recognized, but we’re still unique because we are aware of our own consciousness – we can think about thinking, a “cognitive self-awareness” that is unknown in other animals. Or rather, was unknown, until we made a real effort to look for it.

“The Comparative Psychology of Uncertainty Monitoring and Metacognition,” in the Journal of Behavior and Brain Sciences describes three studies with humans, a group of Rhesus monkeys and one bottlenose dolphin using memory trials. Any animal that didn’t want to complete a particular trial could respond “uncertain.” It turned out that the monkeys and the dolphin used the “uncertain” response in a pattern “essentially identical to the pattern with which uncertain humans use it. Indeed, head researcher David Smith said that “the patterns of results produced by humans and animals provide some of the closest human-animal similarities in performance ever reported in the comparative literature.” He added that the results “suggest that some animals have functional features of, or parallels to, human conscious metacognition.”

In other words, science has repeatedly shown us that our basis for classifying our species as unique and supreme is more thoroughly based in chauvinism than in reality. Ironically, we seem to be irrational about defending our rationality. But why would this be?

Of course part of the problem is the way this information is conveyed, with each scientist proudly (jealously?) proclaiming a conventional-wisdom- busting breakthrough as though no others had occurred, and the mainstream media delivering the story to us as “quirky” or “odd” devoid of larger context. But the other part is that most humans don’t want to entertain the possibility that other animals share most of the characteristics we think of as uniquely human. That’s because it’s only by thinking of animals as unthinking, unfeeling automatons – by insisting that the sun still revolves around the earth – that we can shrug off the enormous harm that our species perpetrates on other animals, cruelly and unnecessarily, each and every day.

If we are to make a case for ourselves as uniquely conscious, the most logical way to prove that might be to abandon “human supremacy” and behave in a way that shows we grasp the larger implications of our species’ actions: To restore ecosystems instead of destroying them; to eat what’s best in the long run for our bodies and our ideals, instead of what’s most immediately handy; to instill in our children a respect for all forms of sentient life.

It’s possible, of course, that we could subsequently find that some animal somewhere has in some way done the same thing, once again redrawing the line. But the effort would not be wasted: At the very least we would have finally lived up to and embodied the term we use to describe ourselves: Humanity.

VANCE LEHMKUHL is a writer and political cartoonist. A collection of his vegetarian cartoons is published as a book, “The Joy of Soy.” Vance is featured as a speaker and entertainer at Vegetarian Summerfest and he has released a CD with his original music group, Green Beings.

References:

Chimps Shown Using Not Just a Tool but a “Tool Kit”, National Geographic News 10/6/04

Capuchins prove we are brothers under the skin, The Telegraph (UK) 9/18/03

Study: Dogs Have Personalities, Discovery News, 12/11/03

Four-legged lifesaver, Tri-City Herald, 10/29/04

Pup shoots man, saves litter mates, Associated Press, 9/9/04

Dogs Understand Language Better Than Expected, Study Finds, Bloomberg News, 6/10/04

Crow Makes Wire Hook to Get Food, National Geographic News, 8/8/02

Intelligence? It’s for the birds, Christian Science Monitor, 9/2/04

Ground squirrels scream ultrasonic warning, CBC News, 7/29/04

Marine Mammals Eavesdrop on Orcas, Discovery News, 11/12/04

Study Shows Shee Have Keen Memory for Faces, Scientific American, 11/9/01

Fast-learning fish have memories that put their owners to shame, The Telegraph (UK), 10/3/04

New UB research finds some animals know their cognitive limits, University at Buffalo Reporter, 12/11/03